The pragmatics of what is said

Ljubljana meets Ducrot

|

| Mr/Ms Argumentics |

More recently there is coverage of formal semantics, with a propositional logic quiz, and lovely explanations of lambda and higher order types.

Relevance Theory and/or Gricean pragmatics; Chomsky on language and mind; and related parts of philosophy of language, philosophy of mind, cognitive psychology, formal semantics and logic.

|

| Mr/Ms Argumentics |

Number and person [on pronouns] interact in interesting ways. One example is the first person plural (‘we’/’us’), which usually picks up from context a set containing the speaker and sometimes but not always containing the hearer too. Some languages mark this inclusive-we/exclusive-we distinction linguistically, either on the verb, or with different forms of the pronoun. For example in Taiwanese, ‘góan’ means we-excluding-you and ‘lán’ means we-including-you. (Allott 2010, p. 57)

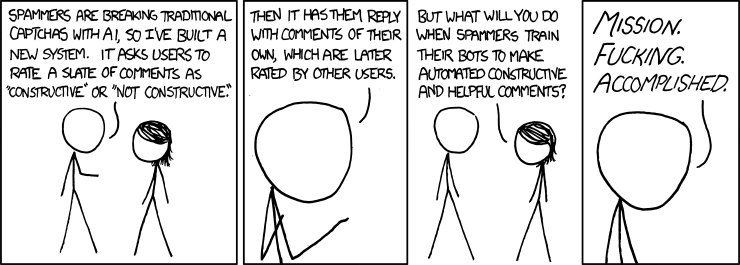

Today's XKCD is really about pragmatics, I think, given that ‘constructive and helpful’ is a pretty good synonym for ‘relevant’.

There are a lot of other XKCDs that are really about pragmatics. One day I'll post a list.

People are beginning to believe now. I think the drop flight two weeks ago, which went beautifully, I think it made people sit up and realize this is really reality.

Reading an interesting review of Shipwreck (or Shipwrecks) (破船 ha sen) by Yoshimura Akira (吉村昭) got me thinking about the meaning of honorifics and about translation.

The reviewer doesn’t say this (and nor do the other reviews available online), but ‘fune’ in ‘o-fune-sama’ is surely ‘boat’ or ‘ship’: ‘舟’ presumably (although there are other characters that mean ‘ship’ and are pronounced ‘fune’). The honorifics ‘o’ and ‘sama’ indicate something like auspiciousness here, I think, so ‘o-fune-sama’ might be translated as ‘the blessing of a boat’, in the sense of a boat received by the village as a kind of gift from higher forces: from the gods, or fate, say. (Cf. ‘In her ninetieth year, Sarah was surprised and delighted to receive the blessing of a child.’)

Honorifics are notoriously difficult to translate. The translator of Shipwrecks obviously judged that with ‘o-fune-sama’ it was best not to try.

Even when a good translation is possible, it often leaves out the honorific dimension. In most contexts v- and t-forms (e.g. ‘vous’ and ‘tu’) are best just translated as ‘you’, as is Spanish ‘usted’ -- a third-person pronoun used to refer to the addressee -- although in very limited contexts (at a barber’s, a tailor’s, or in a PG Wodehouse story) sir might prefer a more literal translation, hmmn? (Of course, English has other, role-specific, third person-ish honorifics: ‘Your Grace’, ‘Mr. President’.)

Returning to Japanese, ‘o-kane’ is just money, not ‘honourable money’ (while ‘kane’ can sound a bit rough and in some contexts might be best rendered into slang: something like ‘dosh’ or ‘the readies’).This demonstrates that the prefix ‘o-’ is sometimes required for polite speech, particularly for those (like women) who are not thought capable of speaking colloquially and politely at the same time.

But Japanese honorifics are particularly context-sensitive in their effects; they don’t always raise the tone. I suspect everyone has to say ‘kami-sama’ or ‘o-kami-sama’, not bare ‘kami’ (god) – or sound mildly blasphemous. But in other cases honorifics can indicate closeness as much as respect. My favourite example, ‘(o-)zou-san’ (lit. (honourable) Mr elephant) is a phrase used by children, those who speak to children, and those who speak to elephants while children are listening. A friend who speaks much more Japanese than me once suggested that ‘o-furo’ (the normal way of saying ‘bath’, but literally ‘honourable [warm] bath’) should be translated ‘lovely hot bath’.

What is the point of all these observations? Partly reinforcing my preexisting beliefs (prejudices) about translation: it is an art, or an applied science, and not a domain which could ever have its own theory. (One of the main contentions of Ernst-August Gutt’s dissertation on relevance theory and translation: published by Blackwell’s – review in the Journal of Linguistics.) It must be a lot of fun.

But also what might be a novel thought. Resistance to translation (and to paraphrase) is supposed to be typical of procedural meaning, exemplified by so-called discourse connectives like ‘so’, ‘then’ and ‘alors’. And it is easy to see how procedural meaning need not contribute to truth conditions, and it is clear that honorifics usually do not: I might have been wrong to tutoyer you, but that doesn’t mean I didn’t refer to you; and ‘o-kane’ and ‘kane’ surely have the same denotation. Perhaps then the semantics of honorifics is procedural. Surely someone must have said this. Relevance theory and the study of polite speech are both popular with people who study pragmatics in Japan. But I can’t find it on the obvious search terms: relevance theory, procedural meaning, honorifics, keigo.

In any case, I’m not convinced. Some questions of politeness and word choice obviously have nothing to do with word meaning in a narrow sense. That a taboo word is forbidden (and in which contexts, to whom, etc.) is a fact about the social status of that word, not something to explain in terms of its semantics. (Very much pace recently fashionable – but in my view daft – accounts of swear words in terms of ‘conventional implicature’, or ‘presupposition’.) Perhaps the same goes for honorifics. It seems to make sense not to postulate any word meaning for honorifics – given that politeness is not necessarily part of speaker meaning, as Mark Jary pointed out some years ago. I wrote in the entry on politeness in my Key Terms book,

“[It is not clear] whether politeness is communicated. Is a speaker who is being polite necessarily, or even usually expressing politeness as part of her speaker meaning? One view is that in being polite a speaker is mainly trying to avoid any implicatures to do with the speaker-hearer’s relationship, by staying within certain parameters of socially acceptable behaviour.”

Compare this with what Mark proposes: a “Relevance Theoretic account of polite verbal behaviour” which:

“distinguishes cases where politeness is communicated from those where it is not, [and] distinguishes the strategic manipulation of expectations of politeness from cases where politeness emerges from the speaker crafting her utterances in such a way as to avoid making manifest assumptions likely to have a detrimental effect on her long term social aims.”

(Last year when I wrote this I hadn’t read Mark’s paper. I should have known about it, though, and I would have put his paper in the list of further reading at the end of the book. It's a good deal more interesting, in my view, than the references on politeness that I did include.)

Regular readers - if there are any - will have been disappointed at the lack of updates and annoyed by the proliferation of spam comments. I have tightened things up so that spurious comments are harder to post and I'll gradually remove the ones that are already here.

As for new posts, I can't promise. I'm trying to get my PhD thesis written, so updates will be infrequent at best. If you use rss, please subscribe to my rss or atom feed so you will see when I do manage a new post without having to check back at the website.

I've been wondering about how to explain and define heuristics lately. I really like this from an interview with programmer Wil Shipley on drunkenblog:

Shipley: One of the rules of writing algorithms that I've recently been sort of toying with is that we (as programmers) spend too much time trying to find provably correct solutions, when what we need to do is write really fast heuristics that fail incredibly gracefully.This is almost always how nature works. You don't have to have every cell in your eye working perfectly to be able to see. We can put together images with an incredible amount of damage to the mechanism, because it fails so gracefully and organically.

This is, I am convinced, the next generation of programming, and it's something we're already starting to see: for instance, vision algorithms today are modeled much more closely after the workings of the eye, and are much more successful than they were twenty years ago.

Interviewer: Wait wait wait, can you elaborate on this heuristics bit being the next big thing, because you just bent some people's brains. When I normally think of heuristics in computer science, I think of either "an educated guess" or "good enough".I.E., a game programmer doesn't have to run out Pi to the Nth degree to calculate the slope of a hill in a physics engine, because they can get something 'good enough' for the screen using a rougher calculation... but hasn't it always been like that out of necessity?

Shipley: Heuristics (the way I'm using them) are basically algorithms that are not guaranteed to get the right answer all the time. Sometimes you can have a heuristic that gets you something close to the answer, and you (as the programmer) say, "This is close enough for government work."This is a very old trick of programming, and it's a very powerful one on its own. Trying to make algorithms that never fail, and proving that they can never fail, is an entire branch of computer science and frankly one that I think is a dead end. Because that's not the way the world works.

When you look at biological systems, they are usually perfect machines; they have all these heuristics to deal with a variety of situations (hey, our core temperature is too hot, let's release sweat, which should cool us off) but none of them are anywhere near provably correct in all circumstances (hey, we're actually submerged in hot water, so sweat isn't effective in cooling us off). But they're good enough, and they fail gracefully.

You don't die immediately if sweating fails to cool you; you just grow uncomfortable and have to make a conscious response (hey, I think I'll get out of this hot tub now).

Programs need to be written this way. In the case of reading bar codes, you don't care if you read garbage a thousand times a second. It doesn't hurt you. If you write an algorithm that looks for barcodes everywhere in the image, even in the sky or in a face or a cup of coffee, it's not going to hurt anything. Eventually the user will hold up a valid barcode, it'll read it, the checksum will verify, and you're in business.

And the barcode recognizer doesn't have to understand every conceivable way a barcode can be screwed up. If the lighting is totally wrong, or the barcode is moving, the user has to take conscious action and, like, tilt the book differently or hold it still. But this kind of feedback is immediately evident, and it's totally natural.

Because I can try 1,000 times a second, I can give immediate feedback on whether I have a good enough image or not, so the user doesn't, like, take a picture, hold her breath for four seconds, have the software go "WRONG," try adjusting the book, take another picture, hold her breath...

Humans are incredibly good at trying new and random things when they get instant feedback. It's the basis of all learning for us, and it's an absolutely fundamental rule of UI design. (This is also the basis of the movement away from having modal dialogs that pop up and say, "Hey, you pressed a bad key!" If you have to pause and read and dismiss the dialog, the lesson you get is, "Stop trying to learn this program," not, "Try a different key."

The Mac and NeXTstep were pioneers in getting this right -- just beep if the user hits a wrong key, so if she wants she can lean on the whole keyboard and see if ANY keys are valid, and there's no punishment phase for it.)

...

If it isn't clear what all this has to do with pragmatics, wait for my PhD thesis...

grice, n. Conceptual intricacy.

"His examination of Hume is distinguished by

erudition and grice." Hence, griceful, adj.

and griceless, adj. "An obvious and griceless

polemic." pl. grouse: A multiplicity of

grice, fragmenting into great details, often in reply to

an original grice note.

Apologies for the long pause. Normal service -- whatever that might be-- is hereby resumed.

The third term is here. No teaching, so I should be dealing with a huge pile of marking and working on my PhD.

Does reading blog posts about the difference between inference and implication count?

Gillian at logicandlanguage.net comments on a point that Gilbert Harman makes in the first chapter of Change in View -- and which has been in the back of my mind all through working on my PhD:

When I was a graduate student at Princeton (many days ago), we used to joke that Gilbert Harman had only three kinds of question for visiting speakers:

- Aren't you ignoring < insert recent result in psychology >?

- Aren't you assuming that there is an analytic/synthetic distincton?

- So you say, < insert one of the speaker's claims >, but isn't that just conflating inference and implication?

...The following claims are ubiquitous and false:

- Logic is the study of the principles of reasoning.

- Logic tells you what you should infer from what you already believe.

Each overstates the responsibilities of logic, which is the study of what follows from what - implication relations between interpreted sentences; one can know the implication relations between sentences without knowing how to update one's beliefs.

Suppose, for example, that S believes the content of the sentences A and B, and comes to realise that they logically imply C. Does it follow that she should believe the content of C? No. Here are two counterexamples:

1. Suppose C is a contradiction. Then she should not accept it. What should she do instead? Perhaps give up belief in one of the premises, but which one? Logic does not answer the question - as we know from prolonged study of paradoxes - because logic only speaks of implication relations, not about belief revision.

2. Suppose she already believes not-C. Then she might make her beliefs consistent by giving up one of the premises, or by giving up not-C. Or she might suspend belief in all of the propositions and resolve to investigate the matter further at a later date.

Hence these questions about inference and belief revision - about what she should believe given i) what she already believes and ii) facts about implication - go beyond what logic will decide. That's not to say that logic is never relevant to reasoning or belief revision, but it isn't the science of reasoning and belief revision. It's the science of implication relations.

Convinced? Gil has a short and very clear discussion of this, and the pernicious consequences of ignoring it, in the second section of his new paper (co-authored with Sanjeev Kulkarni) for the Rutger's Epistemology conference.

This post is not directly related to relevance theory, but it does contain a good joke. In a previous version of this post, I broke with scholarly neutrality for these reasons. It would have made a considerable difference, and it's difficult to keep quiet about these things and stick to academic work when you are wondering if war or the destruction of the environment will end human civilisation first.

From William Gibson's blog:President Bush goes to an elementary school to talk about the war.

After his talk, he offers to answer questions. One little boy puts up his hand and the president asks him his name.

"I'm Billy, sir."

"And what's your question, Billy?"

"I have three questions, sir. Why did the US invade Iraq without the support of the UN? Why are you President when Al Gore got more votes? And whatever happened to Osama Bin Laden?"

Just then the bell rings for recess. Bush announces that they'll continue after recess.

When they return, Bush asks, "OK, where were we? Question time! Who has a question?"

Another little boy raises his hand. The president asks his name.

"I'm Steve, sir."

"And what's your question, Steve?"

"I have five questions, sir. Why did the US invade Iraq without the support of the UN? Why are you President when Al Gore got more votes? Whatever happened to Osama Bin Laden? Why did the recess bell go off twenty minutes early? And what the heck happened to Billy?"

Andone, C. 2003) "Argumentative values of but in the discourse of economics." British and American Studies (Revista de Studii Britanice si Americane) 9: 211-218.

Escuder, A. (1996) "Relevance and translation in writing about environment." Georgica 4: 335-344.

Figueras Solanilla, C. (2002) "La jerarquia de la accesibilidad de las expresiones referenciales en español." Revista Española de Lingüística 32(1): 53-96.

Goerling, F. (1996) "Relevance and transculturation." Notes on Translation 10(3): 49-57.

Gutt, E.-A. (forthcoming) "Relevance-theoretic approaches to translation." In: Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics (2nd edition). Ed. K. Brown. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Kempf, S. (2000) "Who told the truth?" Notes on Translation 14(1): 34-46.

Meunier, J.-P. (1994) "Quelques aspects de l'evolution des theories de la communication: De la signification a la cognition." Degres 79-80: k1-k16.

Moeschler, J. (2004) "Intercultural pragmatics: A cognitive approach." Intercultural Pragmatics 1(1): 49-70.

http://www.degruyter.de/journals/intcultpragm/pdf/1_49.pdf

Murillo, S. (2004) "A relevance reassessment of reformulation markers." Journal of Pragmatics 36(11): 2059-2068.

(updated reference)

Pilkington, A. (2001) "Non-lexicalised concepts and degrees of effability: Poetic thoughts and the attraction of what is not in the dictionary." Belgian journal of Linguistics 15: 1-10.

Ram, A. (1990) "Knowledge goals: A theory of interestingness." In: Proceedings of the 12th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society. Cambridge, MA, August.

Available here

Recanati, F. (2003b) "Embedded implicatures." Philosophical Perspectives 17(1): 299-332.

Adobe Acrobat format:

http://www.bol.ucla.edu/~schlenke/Recanati-Embedded.pdf

Rich Text format:

Available here

Schank, R.C. (1979) "Interestingness: Controlling inferences." Artificial Intelligence 12: 273-297.

Silva, F.-A. (1996) "Lancando anzois: Uma analise cognitiva de processos mentais em traduçao." Revista de Estudos da Linguagem (RevEL) 4(2): 71-90.

Storto, L. (2004) "Review of F. Recanati's Literal Meaning." The Linguist List 15.2535, 11-9-2004.

http://linguistlist.org/issues/15/15-2535.html

Yus, F. (forthcoming) "Relevance theory." In: Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics (2nd edition). Ed. K. Brown. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Ziv, Y. (1996b) "Pronominal reference to inferred antecedents." Belgian Journal of Linguistics 10: 55-67..